#31: Open-Source Software in the Age of AI

Everything I believed about software has changed rapidly over the past few years. AI tools like Codex, Cursor, and Claude Code are making development vastly faster and more accessible. The value of traditional software businesses is cratering,1 and the far-and-away most important software assets are no longer code, but model weights.

These changes also extend to open-source software, our great collective project that underpins technology everywhere. Over the last few weeks, I’ve seen projects like tldraw change how open-source software is written, and openclaw change how it is utilized. These are important changes, not just for open-source aficionados like myself. In this blog post, I’ll make some predictions: the future will have a lot more open-source software, written by machines but funded by people, giving better experiences and greater freedom to the consumer.

Creation of Open-Source Software

The term open-source means the source code of such software is published for anyone to read, modify, and redistribute. This key tenet provides several important benefits:

Trust: anyone can audit the software and raise issues;

Free as in freedom: anyone can edit their copy of the software as they please;

Collaboration: anyone can publish their modified versions of the software;

Free as in beer: it doesn’t cost any money!

This puts open-source software (OSS) in a neat intersection of the personal and the professional. People contribute to it in areas of their interest; OSS is a patchwork of passion projects. While those engineers are not doing it for money, the experience gained by this work, and the respect it confers, becomes a professional advantage.

Many junior engineers, myself once included, took their first steps into “real” engineering by making small contributions to open-source projects. But today, many open-source projects are considering closing themselves to contributions:

As the author of tldraw explains, AI coding tools are leading to a proliferation of very inexperienced developers using AI to generate massive, poorly-formed PRs (requests to contribute code to a project), which drain time and attention from the maintainers, who need to review those requests.

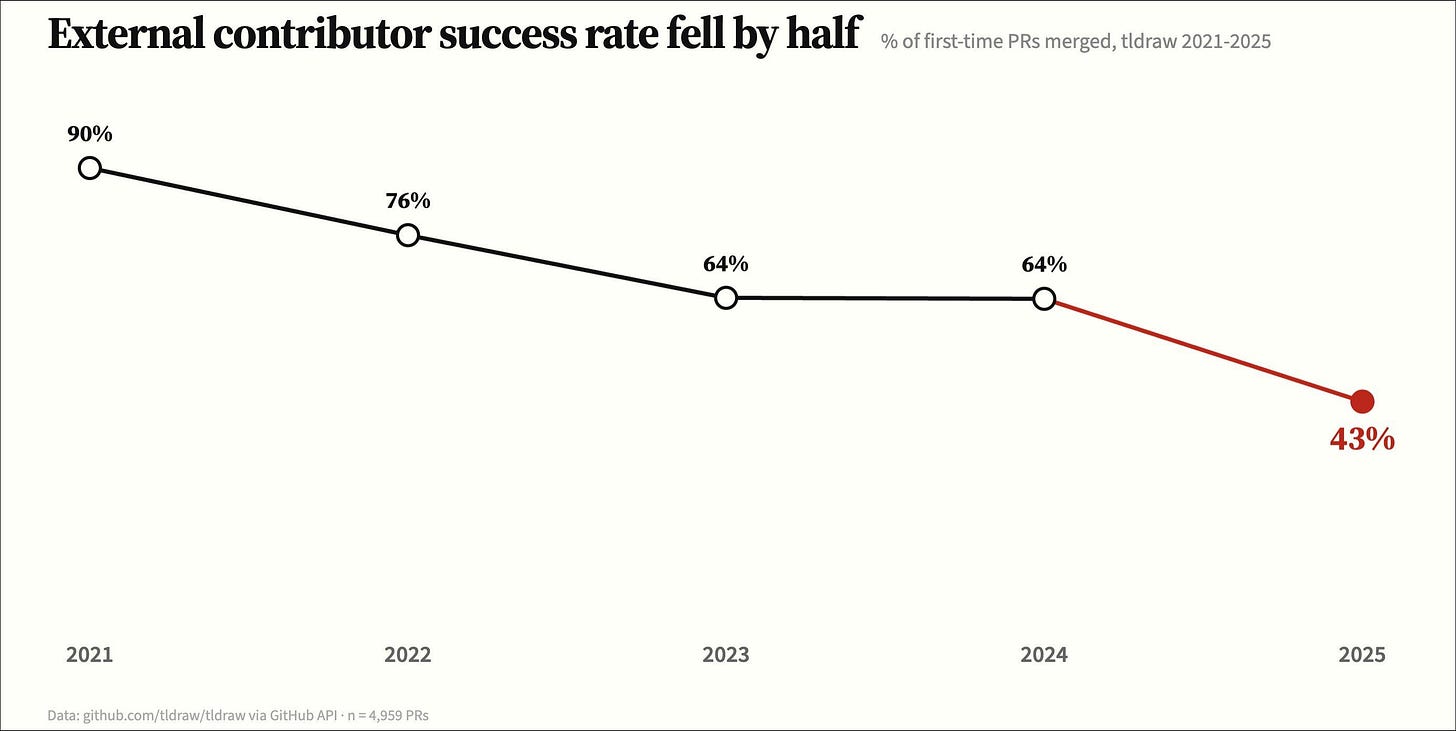

Previously, low-quality contributions had always been an issue, but they were kept in check by the fact that writing them still took significant time and effort, much more than reviewing them. For tldraw, Pradyumna Prasad ran the numbers: PRs by external contributors went from 90% acceptance in 2021 to 43% in 2025 — nearly a 6x increase (10% → 60%) in bad submissions, an overwhelming quantity.

There are a few clear ways to address this problem.

Projects could use AI tools like Greptile to automatically review PRs, and stem the tide of junk. But those cost money, which OSS projects usually don’t have.

Projects can do some gatekeeping and set a more requirements-heavy process for first-time contributors.

Projects could close their doors to code contributions altogether and only accept monetary contributions.

The third bullet here might sound crazy, but it’s not that far off. Many skilled engineers already report basically no longer writing code, but just interfacing with AI to define the job to be done, and then letting the AI run with it. This means that the leverage provided by money (to purchase AI tokens) on top of the time of a skilled developer is growing significantly. SemiAnalysis reports that already 4% of public GitHub commits are written by Claude Code today.

Additionally, the open-source development model where anyone can try to contribute is also under strain from supply chain attacks, in which malicious contributors try to hide sophisticated malware in open-source software. Similar to the deluge of low-quality PRs: we should expect this to increase due to the ease of AI code generation.

Given these trends, we may expect a world in which projects are closed-by-default to outside contributions, and a small group of trusted maintainers mostly direct AI to make contributions by spending donated funds. This would also make donations more appealing for donors, because they could direct the funds more precisely — instead of a general-purpose $20 donation, you could direct those dollars to buy AI tokens to make a specific change.

If the future of open-source software is therefore basically crowdfunding, then this would be a tremendous accelerant: right now, the creation of open-source software is constrained by the spare-time throughput of a small number of skilled humans. But if it becomes easy and accessible to contribute small amounts of money to creating the software that everyone2 wants, then this ecosystem will grow by orders of magnitude overnight. There is no way that proprietary systems would be able to keep up. It will finally be The Year of Linux on the Desktop.

Utilization of Open-Source Software

Open-source came about in the earliest days of computing, when all software, and the data it used, lived on your computer. But around 2010, mobile and the shift to cloud changed this dynamic: suddenly your software was online, and the data not on your disk, but on some faraway server.

This made it harder for open-source software to succeed, because even if you wanted to use it, you might not be able to get your data from a proprietary service and use it in an open-source client. The shift to cloud meant an emergence of walled gardens, where users are not free to port their data to competing services.

Some enthusiasts3 wished for a return to the prior paradigm, in which users could possess all their data on their computers, and provide that data, only as needed, to third-party cloud services. There are a lot of good things about this — privacy, security, ownership — but most users don’t care much, and the level of engineering required to implement API interfaces for every single service makes it impractical.

However, in our burgeoning AI era, this dream lives:

Many cloud software products that would operate on your data can be easily replicated with AI coding tools;

AI is amazingly good at implementing on-the-fly API interfaces to services, making it easy to pull all your data from a service to your disk, or to conversely upload it.

What we saw with openclaw is that it is viable to pull your entire context to your machine, give it to an AI agent, and let it rip. A variant of the bitter lesson strikes again: having everything in one place and letting the AI munge it is both more general and more performant than painstakingly curating a bunch of special-cased behavior.

There is now a point to having all your data on your disk that goes beyond abstract trust, privacy, security, or long-term ownership: having all your data will make your AI provide better results! I suspect that in coming years, we’ll see a great repatriation of user data from lots of fragmented services into just one place — either a cloud repository that they control, or to their own hardware.

Having overcome the walled garden problem, this creates opportunities for open-source software4 to operate on the user’s data. But what’s going to be operating most heavily on the user’s data? Well, AI models, of course. And those can be either proprietary (like OpenAI or Anthropic today) or open-source — ones that you can run yourself.

Open-Source Models

What does it mean for an AI model to be open-source? A model is not just determined by its source code. The authors would have to make available the model weights, training code, inference code, and training data. The training data is a tall bar to clear, because it’s usually legally messy.5 For that reason, the most prominent “open” models like Kimi, Qwen, and Llama are predominantly open-weight.

On the one hand, this violates some core principles of open-source: if you can’t reproduce it, then you can’t audit it. There’s a significant problem in not knowing how your model was trained: what if it was built to suppress certain types of information? However, this may not be that severe an issue in reality, because you can build evaluations to test the quality of the model. For example, it would be very easy to figure out if a model has been trained not to speak of Tiananmen Square: just ask it.

But on the other hand, an open-weight model still is enormously empowering from an open-source perspective: you can run it privately, trustlessly, on your home computer.6 And between algorithmic and hardware improvements, the quality of home model performance will become better every year.7 It’s well possible that this ends up sufficient for personal purposes.8

Conclusion

There’s a good chance we are moving into a golden era of open-source software. It is faster and easier than ever for people around the globe to collaborate in calling great software into reality, and the accessibility of this creative process — all you need is taste and a little bit of money — is increasing dramatically.

Further, the explosive capability of AI to both pull data from, and make obsolete, traditional cloud software, means that we may see a paradigm shift: data back to the user’s own disk. The user will benefit greatly from having all their personal context in one place for AI to consume and analyze. Finally, for many cases, the AI that runs on this data may take the form of a fully locally hosted open-weight model.

All in all, this is tremendously hopeful for open-source values. What we’ve described above will return sovereignty, freedom, privacy, and trustlessness to consumers everywhere. It looks tremendously empowering for the individual. It is bearish for proprietary software that will struggle both financially to compete in this paradigm, and in terms of feature parity with these open-source projects that we should expect to grow in scope by orders of magnitude.

For public SaaS companies, Enterprise-value-to-revenue multiples went from 15-20x in 2021 to 5-8x today.

By which I don’t mean one-size-fits-all software for everyone, but endless variations to suit every person’s preferences.

For example, the homelab community, or the Urbit project.

This applies to open-source software that’s hosted in either the cloud or locally on the user’s computer. However, if the user has all their data on their computer, then the software would likely be run on their computer, too, because:

This avoids a slow upload/download cycle, and preserves the user’s privacy.

Conventionally, when open-source software is offered as optionally cloud-hosted, that is a monetization technique: it essentially charges for handling installation, maintenance, and managing the user’s data.

I.e. the training data is scraped under some level of legal controversy, or perhaps licensed as part of an exclusive agreement, etc. Very hard to re-distribute.

You may need a few thousand dollars’ worth of computing equipment depending on the speed of inference that you want.

That’s not even to mention the possibility of eventually training your own models. If training algorithms improve enough, you may be able to train your own models, using only small amounts of data. For example, Andrej Karpathy has been building GPT-2 at home routinely over the years and achieved enormous efficiency improvements along the way

I think of this as similar to other historical computing constraints: twenty years ago, internet speeds and hard drive sizes were insufficient for consumers. But improvements in the underlying technologies added orders of magnitude of capacity — and though consumer utilization increased, it did so in a way that’s ultimately limited: consumers did not make thousands of times more Microsoft Word documents than before. File sizes of images did not increase. Normal consumers store only so much 4K video because there’s only so much that they have the time to watch, and so forth. In a similar vein, the consumer-level (not corporate!) demand for AI may grow more slowly than the underlying technologies add capacity. I only generate so much data to be analyzed.